Babyloniaca Book 1

“What, then, does it mean for Berossos to introduce himself as a Babylonian, and a priest of Bel? The question may seem odd, for it suggests a choice which prima facie Berossos did not have: was he not simply stating a fact?

And yet, I shall argue that Berossos did have a choice as to how he presented himself, and that both his profession as a priest and his self-portrayal as a Babylonian can be read as examples of carefully calibrated role play.

Let us first have a look at ethnicity. As a Babylonian, Berossos was a barbarian in Greek eyes, and broadly speaking that was not an auspicious starting point. Yet, non-Greek cultures could also carry more positive connotations.

By the Hellenistic period, Greek intellectuals had become accustomed to regard barbarian priests as commanding a privileged knowledge of history. Berossos very directly plays on that stereotype when he rejects the untruths spread by ‘Greek writers’ in Babyloniaca Book 3.

Greek readers would have appreciated that, as a priest of Bel, Berossos was in a good position to set the record straight; though the gesture would have had little resonance in a purely Mesopotamian context.

Indeed, we now know that from a Mesopotamian perspective there was no such thing as ‘a priest of Bel’ in Babylon, though there was of course a wide range of personnel associated with the main temple of Marduk, the Esagila.

Berossos, then, does not simply state a neutral fact when he introduces himself as a Babylonian and a priest of Bel. Rather, he masquerades as a figure from Greek orientalising lore so as to lodge a very specific claim to cultural authority: Babylonian priests (‘Chaldaeans’, as they were known), were not just seen as masters of time but also as sources of esoteric knowledge, essentially a society of proto-philosophers.

That cliche, I suggest, informs Berossos’ paraphrase of Enūma Eliš in Babyloniaca Book 1.

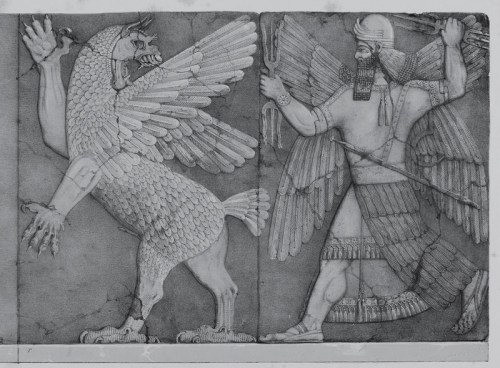

Battle between Marduk (Bel) and Tiamat. Drawn from a bas-relief from the Palace of Ashur-nasir-pal, King of Assyria, 885-860 B.C., at Nimrûd.

British Museum, Nimrûd Gallery, Nos. 28 and 29.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/06/tablet-of-destinies.html

In his account of creation, Berossos describes the universe as being created from two main forces, Tiamat and Bel. Tiamat provides the matter from which Bel shapes all things. She is female, he is male; she is passive, he is active; she is chaotic, dark and watery, he is orderly, active, bright and airy.

In Babylonian terms, this is not a bad paraphrase of Enūma Eliš, though it skips over the opening genealogies and radically condenses the rest of the narrative. Much of this work of condensation will be down to Alexander Polyhistor, the first-century BCE excerptor who had little incentive to preserve details of Berossos’ account that did not suit his sensationalist agenda.

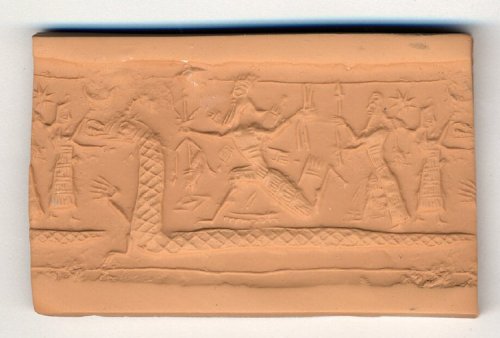

British Museum 89589.

A black serpentinite cylinder seal in the linear style portrays a snout-nosed, horned reptile, probably Tiamat as a dragon. The upper third of its long body rises from two front paws or hands, one of which is raised; the remainder of the body runs around the bottom of the seal and supports three figures; there are no hind legs.

A bearded god, Ninurta or Bel-Marduk, runs along the reptile’s body with crossed, wedge-tipped quivers on his back. In his right hand he holds a six-pronged thunderbolt below which is a rhomb, while in his left he holds two arrows.

Behind the god, a smaller bearded god in a horned head-dress holds a spear before him.

On the tail of the reptile stands a goddess, who holds her arms open to seize the snout of the reptile.

To the left of her head is the eight-rayed star of Istar and the inverted crescent of the Moon God Sin.

The seal may illustrate a scene from the epic of creation in which the forces of chaos, led by Tiamat, are defeated by a god representing cosmic order, Ninurta, or Bel-Marduk.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=159863&objectId=277961&partId=1

But even the truncated version of Babyloniaca Book 1 which Polyhistor passed on to Eusebius still betrays signs of Berossos’ original approach. What Berossos seems to have done in Babyloniaca Book 1 is to extract two cosmic principles from the jumble of divine characters in Enūma Eliš.

The resulting account of creation strikingly resembles Stoic physics as formulated by Berossos’ contemporary Zeno of Citium. For Zeno too, the universe was based on two entities, matter and god.

Like Bel in Berossos, Zeno’s god was active, male, the shaping principle that pervaded matter; and like Berossos’ Tiamat, Stoic matter was passive, female, waiting to be dissected and moulded.

Sceptics may object that this convergence between Berossos and Zeno may as well be pure coincidence; after all, there are only so many ways one can imagine a cosmogony, and the opposition between Marduk and Tiamat was of course prefigured in Enūma Eliš itself.”

Johannes Haubold, “The Wisdom of the Chaldaeans: Reading Berossos, Babyloniaca Book 1,” from Johannes Haubold, Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Robert Rollinger, John Steele (eds.), The World of Berossos, Proceedings of the 4th International Colloquium on the Ancient Near East Between Classical and Ancient Oriental Traditions, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2013, pp. 34-5.