Babylonian Astro-Theology

“In the Observations of Bel the stars are already invested with a divine character. The planets are gods like the sun and moon, and the stars have already been identified with certain deities of the official pantheon, or else have been dedicated to them.

The whole heaven, as well as the periods of the moon, has been divided between the three supreme divinities, Anu, Bel and Ea. In fact, there is an astro-theology, a system of Sabaism, as it would have been called half a century ago.

The star constellation of Hydra as a Babylonian Serpent-Dragon called Mushussu meaning “furious snake,” with horns and wings from a clay cuneiform tablet of the Persian period.

According to Professor Langdon, Tammuz (Sumerian Dumuzi) was called a “Heavenly Serpent-dragon,” he also noted that Ningishzida whose name means “Lord of the Good Tree” according to some scholars, was an aspect of Dumuzi/Tammuz, Dumuzi being called in hymns “Damu, the child Ningishzida.”

(For the drawing cf. p. 286. Stephen Herbert Langdon. The Mythology of All Races- Semitic. Vol. 5. Boston. Marshall Jones Company. 1931).

http://www.bibleorigins.net/SerpentDragonMardukAsshur.html

This astro-theology must go back to the very earliest times. The cuneiform characters alone are a proof of this. The common determinative of a deity is an eight-rayed star, a clear evidence that at the period when the cuneiform syllabary assumed the shape in which we know it, the stars were accounted divine.

We have seen, moreover, that the sun and moon and evening star were objects of worship from a remote epoch, and the sacredness attached to them would naturally have been reflected upon the other heavenly bodies with which they were associated.

Totemism, too, implies a worship of the stars. We find that primitive peoples confound them with animals, their automatic motions being apparently explicable by no other theory; and that primitive Chaldea was no exception to this rule has been already pointed out.

Here, too, the sun was an ox, the moon was a steer, and the planets were sheep. The adoration of the stars, like the adoration of the sun and moon, must have been a feature of the religion of primeval Shinar.

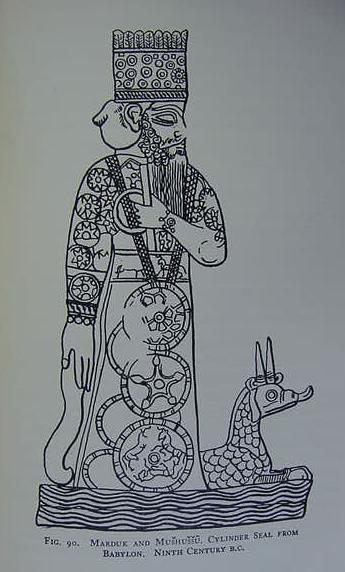

Marduk, the supreme god of Babylon. At his feet the Mushhushshu Serpent-dragon, associated with him, as he overpowered it when he defeated Tiamat the female personification of the salty sea or ocean, mother of the gods, who sought to destroy the land-dwelling gods until killed by Marduk.

In this myth the Serpent-dragon was a creature of Tiamat’s (for the image cf. p. 301. Stephen Herbert Langdon. The Mythology of All Races- Semitic. Vol. 5. Boston. Marshall Jones Company. 1931).

This drawing is after a 9th century BCE Babylonian cylinder seal. The Assyrians later declared their God Asshur as the god who defeated Tiamat, and Marduk’s serpent-dragon was portrayed as accompanying Asshur. Marduk’s robe is the heavenly night sky with all its stars. he was also called “the son of the Sun,” “the Sun” and “bull-calf of the Sun” (Babylonian amar-utu). I suspect that the medallions hanging from his neck are none other than the Tablets of Fate.

http://www.bibleorigins.net/SerpentDragonMardukAsshur.html

But this primeval adoration was something very different from the elaborate astro-theology of a later day. So elaborate, indeed, is it that we can hardly believe it to have been known beyond the circle of the learned classes.

The stars in it became the symbols of the official deities. Nergal, for example, under his two names of Sar-nem and ‘Sulim-ta-ea, was identified with Jupiter and Mars. It is not difficult to discover how this curious theological system arose.

Its starting-point was the prominence given to the worship of the evening and morning stars in the ancient religion, and their subsequent transformation into the Semitic Istar. The other planets were already divine; and their identification with specific deities of the official cult followed as a matter of course.

As the astronomy of Babylonia became more developed, as the heavens were mapped out into groups of constellations, each of which received a definite name, while the leading single stars were similarly distinguished and named, the stars and constellations followed the lead of the planets. As Mars became Nergal, so Orion became Tammuz.

The priest had succeeded the old Sumerian sorcerer, and was now transforming himself into an astrologer. To this cause we must trace the rise of Babylonian astro-theology and the deification of the stars of heaven.

The Sabianism of the people of Harrân in the early centuries of the Christian era was no survival of a primitive faith, but the last echo of the priestly astro-theology of Babylonia. This astro-theology had been a purely artificial system, the knowledge of which, like the knowledge of astrology itself, was confined to the learned classes.

It first grew up in the court of Sargon of Accad, but its completion cannot be earlier than the age of Khammuragas. In no other way can we explain the prominence given in it to Merodach, the god of Babylon.”

A.H. Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians, 5th ed., London, 1898, pp. 400-2.