Selz: Enūma Anu Enlil and MUL.APIN

“My contribution is an outsider’s view, neither pretending to do justice to the ongoing discussions in biblical studies, in particular in the studies of the Dead Sea Scrolls, nor dwelling on the highly complicated matter of the Babylonian background of the astronomical Enoch tradition.

O. Neugebauer, one of the pioneers working on Babylonian astronomical texts wrote in 1981:

“The search for time and place of origin of this primitive picture of the cosmic order can hardly be expected to lead to definitive results. The use of 30-day schematic months could have been inspired, e.g., by Babylonian arithmetical schemes (of the type of ‘Mul-Apin’), or by the Egyptian calendar.”

He then continues: “But [sc. in Astronomical Enoch] there is no visible trace of the sophisticated Babylonian astronomy of the Persian or Seleucid-Parthian period.”

The Neo-Assyrian star map K 8538, from H. Hunger, ed., Astrological Reports to Assyrian Kings (SAA 8, Helsinki: Helsinki University Press: 1992), p. 46.

K8538 is held in the British Museum collection, excavated by Austen Henry Layard from the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

The curator’s comments state that the text and depicted constellations are interpreted in Koch, 1989.

A celestial planisphere with eight sections, representing the night sky of 3-4 January 650 BCE over Nineveh.

Also Figure 1, Gebhard Selz, Of Heroes and Sages, p. 785. http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=303316&partId=1

(Cf. M. Albani, Astronomie und Schöpfungsglaube: Untersuchungen zum astronomischen Henochbuch (WMANT 68; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirche 1994), pp. 1-29; cf. furthermore the works of Milik, Books of Enoch, and O. Neugebauer, The “Astronomical” Chapters of the Ethiopic Book of Enoch (72 to 82) Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab: Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser 40.10; Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1981).

The opinion “that the astronomical part of the Book of Enoch is based on concepts extant in the Old Testament is simply incorrect: the Enoch year is not an old semitic calendaric unit; the schematic alternation between hollow and full months is not a real lunar calendar, and there exists no linear scheme in the Old Testament for the length of daylight, or patterns for ‘gates,’ for winds, or for ‘thousands’ of stars, related to the schematic year. The whole Enochian astronomy is clearly an ad hoc construction and not the result of a common semitic tradition.

Neugebauer’s opinion sharply contrasts the statement of VanderKam that “Enoch’s science is a Judaized refraction of an early stage in the development of Babylonian astronomy—a stage that finds varied expression in texts such as the astrolabes, Enūma Anu Enlil, and mul APIN.

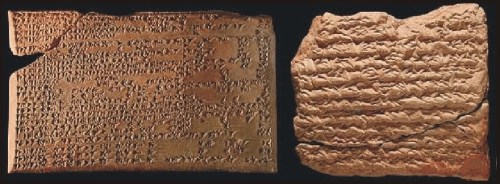

Enuma Anu Enlil is a series of about 70 tablets dealing with Babylonian astrology. These accounts were found in the early 19th century by excavation in Niniveh, near present day Bagdad. The bulk of the work is a substantial collection of omens, estimated to number between 6500 and 7000, which interpret a wide variety of celestial and atmospheric phenomena in terms relevant to the king and state. The tablets presumably date back to about 650 BCE, but several of the omens may be as old as 1646 BCE. Many of the reports found on the tablets represent ‘astrometeorological’ forecasts (Rasmussen 2010).

http://www.climate4you.com/ClimateAndHistory%205000-0%20BC.htm

In it astronomical and astrological concepts are intermingled and schematic arrangements at times predominate over facts.”

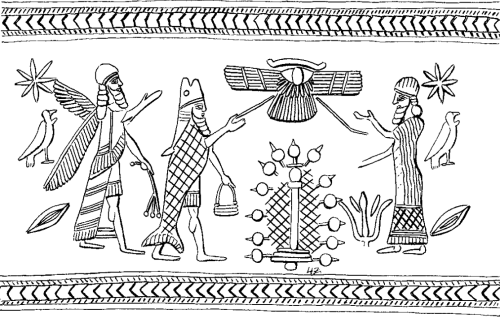

Here VanderKam comes back to an early view of H. Zimmern from 1901, who saw the Enochic tradition anchored in stories around the primeval king Enmeduranki, to whom the gods granted mantic (related to divination or prophecy) and astronomical wisdom.

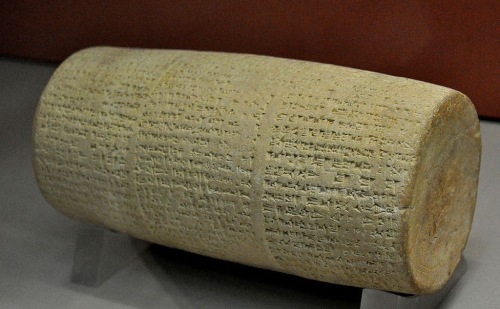

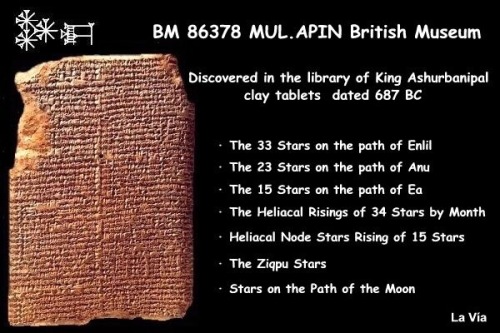

BM 86378, cuneiform tablets from the library of King Ashurbanipal, circa 687 BCE, held in the British Museum.

MUL.APIN includes a list of thirty-six stars, three stars for each month of the year. The stars are those having a helical rise in a particular month. The first line lists the three stars, which have the helical rise in the first month of the year, Nisannu, which is associated with the vernal equinox.

In the second line, three other stars are listed, with a helical rise in the second month, Ayyāru, and so on.

I MUL.APIN sono testi antichi su tavolette di argilla, comprendono un elenco di trentasei stelle, tre stelle per ogni mese dell’anno.

Le stelle sono quelle aventi ciascuna la levata eliaca in un particolare mese. Si ha perciò questo schema: nella prima riga sono elencate tre stelle, che hanno la levata eliaca nel primo mese dell’anno, Nīsannu (quello associato all’epoca dell’equinozio di primavera).

Nella seconda riga sono elencate altre tre stelle, ancora ciascuna avente levata eliaca nel secondo mese, Ayyāru, e così via.

http://www.lavia.org/italiano/archivio/calendarioakkadit.htm

(VanderKam, Enoch and the Growth, p. 101. H. Zimmern, Beiträge zur Kenntnis der babylonischen Religion: Die Beschwörungstafeln Šurpu, Ritualtafeln für den Wahrsager, Beschwörer und Sänger (Assyriologische Bibliothek 12; Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1901).

The main arguments against Neugebauer’s position are provided by the Enochic Aramaic fragments from Cave 4, the careful evaluation of which prompted Milik already in 1976 to suggest that the astronomical parts of the Enoch tradition do belong to the oldest stratum of the Enoch literature in concordance to the (originally) year life span allotted to Enoch in Genesis 5:23.”

Gebhard J. Selz, “Of Heroes and Sages–Considerations of the Early Mesopotamian Background of Some Enochic Traditions,” in Armin Lange, et al, The Dead Sea Scrolls in Context, v. 2, Brill, 2011, pp. 784-6.