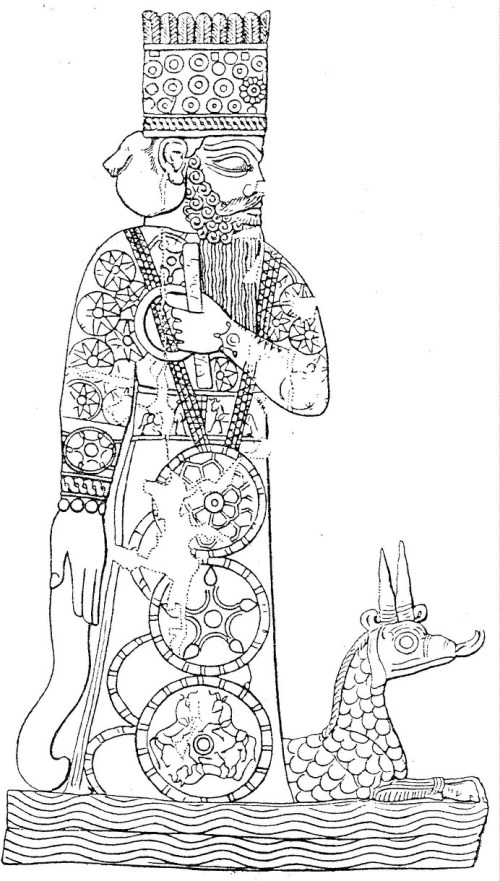

Marduk, Sun God

“On the first day of the Babylonian New Year an assembly of the gods was held at Babylon, when all the principal gods were grouped round Merodach in precisely the same manner in which the King was surrounded by the nobility and his officials, for many ancient faiths imagined that the polity of earth merely mirrored that of heaven, that, as Paracelsus would have said, the earth was the microcosm of the heavenly macrocosm—“as above, so below.”

The ceremony in question consisted in the lesser deities paying homage to Merodach as their liege lord. In this council, too, they decided the political action of Babylonia for the coming year.

It is thought that the Babylonian priests at stated intervals enacted the myth of the slaughter of Tiawath. This is highly probable, as in Greece and Egypt the myths of Persephone and Osiris were represented dramatically before a select audience of initiates.

We see that these representations are nearly always made in the case of divinities who represent corn or vegetation as a whole, or the fructifying power of springtime. The name of Merodach’s consort Zar-panitum was rendered by the priesthood as ‘seed producing,’ to mark her connexion with the god who was responsible for the spring revival.

Merodach’s ideograph is the sun, and there is abundant evidence that he was first and last a solar god. The name, originally Amaruduk, probably signifies ‘the young steer of day,’ which seems to be a figure for the morning sun.

He was also called Asari, which may be compared with Asar, the Egyptian name of Osiris. Other names given him are Sar-agagam, ‘the glorious incantation,’ and Meragaga, ‘the glorious charm,’ both of which refer to the circumstance that he obtained from Ea, his father, certain charms and incantations which restored the sick to health and exercised a beneficial influence upon mankind.

Merodach was supposed to have a court of his own above the sky, where he was attended to by a host of ministering deities. Some superintended his food and drink supply, while others saw to it that water for his hands was always ready.

He had also doorkeepers and even attendant hounds, and it is thought that the satellites of Jupiter, the planet which represented him, may have been dimly visible to those among the Chaldean star-gazers who were gifted with good sight.

These dogs were called Ukkumu, ‘Seizer,’ Akkulu, ‘Eater,’ Iksuda, ‘Grasper,’ and Iltehu, ‘Holder.’ It is not known whether these were supposed to assist him in shepherding his flock or in the chase, and their names seem appropriate either for sheep-dogs or hunting hounds.”

Lewis Spence, Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria, 1917, pp. 201-2.