Kvanvig: Assurbanipal Studied Inscriptions on Stone from Before the Flood

“The first thing to notice is the strange expression salmīšunu, “their images.” The pronoun refers back to the primeval ummanus / apkallus. They had “images,” created by Ea on earth. A line from Bīt Mēseri sheds light on the issue.

šiptu šipat Marduk āšipu salam Marduk

“The incantation is the incantation of Marduk, the āšipu is the image of Marduk.”

(Bīt Mēseri II, 226. Cf. Gerhard Meier, “Die zweite Tafel der Serie bīt mēseri,” AfO 14, 1941-4, pp. 139-52, 150).

In his role as exorcist, the āšipu is here an image of the deity itself. In the Poem of Erra something similar must have been thought. The āšipu and other priests with responsibility for the divine statues were the earthly counterparts of the transcendent ummanus / apkallus. They were their images on earth.

“Sometimes animal hybrids … appear to take part in rituals….some types are clearly minor deities, since they wear the horned cap as a mark of their divinity…others may be human. A …winged god, standing or kneeling, holds a bucket and cone … in the scenes of “ritual” centered on the stylized tree. A similar female figure holds a chaplet of beads….A third figure carries a flowering branch, sometimes also a sacrificial (?) goat. Sometimes he wears the horned cap, and even when does not he often has wings. Presumably, therefore, such figures are also non-mortal; they may represent the Seven Sages in human guise.”

From Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, 1992, pp. 86-8.

We must admit that the following text from line 34 is not very clear. Does the ummanus from line 34 mean the primeval apkallus, or does it refer to the priests as ummanus? If we follow the interpretation underlying Foster’s translation, the second option is preferable.

“He himself gave those same (human) craftsmen

great discretion and authority;

he gave them wisdom and great dexterity.

They have made (his) precious image radiant,

even finer than before.”

(Poem of Erra II, pp. 34-6. Foster, Before the Muses, p. 892).

The text thus describes how Ea equips the earthly ummanus with wisdom and dexterity to make them able to restore Marduk’s statue.

To care for the divine statue, to make sure that it is qualified for the manifestation of the divinity, is to secure cosmic stability. This was the great responsibility of the āšipu when they acted as earthly images of the apkallus, the guardians of the cosmic order.

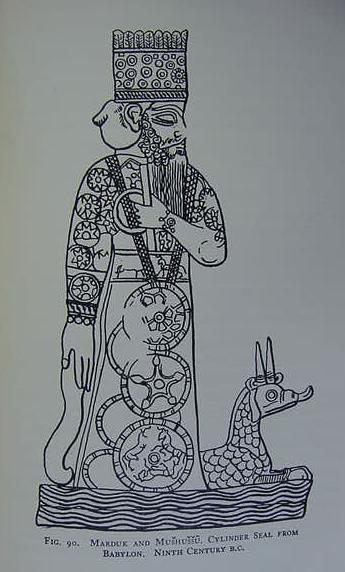

Marduk, the supreme god of Babylon. At his feet the Mushhushshu Serpent-dragon, which he overpowered when he defeated Tiamat, mother of the gods, who sought to destroy the land-dwelling gods.

In this myth the Serpent-dragon was a creature of Tiamat’s (for the image cf. p. 301. Stephen Herbert Langdon. The Mythology of All Races- Semitic. Vol. 5. Boston. Marshall Jones Company. 1931).

This drawing is after a 9th century BCE Babylonian cylinder seal. The Assyrians later declared their God Asshur as the god who defeated Tiamat, and Marduk’s serpent-dragon was portrayed as accompanying Asshur.

Marduk’s robe depicts the heavenly night sky with all its stars.

I believe that the circular medallions hanging from his neck are among the few portrayals of the me, the tablets of destinies, in all Assyrian art.

Marduk was also called “the son of the Sun,” “the Sun” and “bull-calf of the Sun” (Babylonian amar-utu).

http://www.bibleorigins.net/SerpentDragonMardukAsshur.html

The supreme responsibility on earth for cosmic stability rested on the king. Therefore the king needed to be depicted as wise, having insight into the hidden laws of the cosmos. This is a reoccurring topic in descriptions of kings and their own self-presentations.

It reaches as far back as the third millennium, but shows an increasing tendency in the first millennium.

(Cf. R.F.G. Sweet, “The Sage in Akkadian Literature: A Philological Study,” in The Sage in Israel and the Ancient Near East, eds. J.G. Gammie and L.G. Perdue, Winona Lake, 1990, pp. 45-65, 51-7).

In their boasting of superior wisdom the kings of the first millennium compared their own wisdom with the wisdom of the primary apkallu, Adapa:

“Sargon claims to be: “a wise king, skilled in all learning, the equal of

the apkallu, who grew up in wise counsel and attained full stature in good judgement.”

(Cylinder Inscription, 38. Cf. David Gordon Lyon, Keilschriftentexte Sargon’s Königs von Assyrien, (722-705 v. CHR), AB. Leipzig, 1883, pp. 34-5. Translation according to Sweet, “The Sage in Akkadian Literature,” p. 53).

“Sennacherib presents himself as one to whom “Ninšiku gave wide understanding and equality with the apkallu, Adapa, and granted profound wisdom.”

(Bull Inscription, 4. Cf. D.D. Luckenbill, The Annals of Senacherib, Chicago, 1924, p. 117; translation according to Sweet, “The Sage in Akkadian Literature,” p. 53).

Prism of Sennacherib, the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago.

Daniel David Luckenbill, The Annals of Sennacherib, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1924.

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oip2.pdf“Assurbanipal describes his comprehensive wisdom in the following way:

“Marduk, the apkallu of the gods, gave me wide understanding and extensive intelligence (and) Nabu, the scribe (who knows) everything, granted me his wise teachings ….

I have learned the art of the apkallu, Adapa, (so that now) I am familiar with the secret storehouse of all scribal learning, (including) celestial and terrestrial portents.

I can debate in an assembly of ummanus and discuss with the clever apkal šamni (oil diviners) (the treatise) “if the liver is a replica of the sky.” I used to figure out complicated divisions and multiplications that have no solutions.

Time and again I have read the cleverly written compositions in which the Sumerian is obscure and the Akkadian is difficult to interpret correctly.

I have studied inscriptions on stone from before the Flood which are sealed, obscure and confused.”

(Tablet L4 obv. I, 10-8. Cf. M. Streck, Assurbanipal und die letzen assyrischen König bis zum Untergange Nineveh’s, vol. II, Leipzig, 1916, 254-7.)

Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011, pp. 138-9.