” … Then returning to the dead body of Tiâmat he smashed her skull with his club and scattered her blood to the north wind, and as a reward for his destruction of their terrible foe, he received gifts and presents from the gods his fathers.

The text then goes on to say that Marduk “devised a cunning plan,” i.e., he determined to carry out a series of works of creation.

He split the body of Tiâmat into two parts; out of one half he fashioned the dome of heaven, and out of the other he constructed the abode of Nudimmud, or Ea, which he placed over against Apsu, i.e., the deep.

He also formulated regulations concerning the maintenance of the same. By this “cunning plan” Marduk deprived the powers of darkness of the opportunity of repeating their revolt with any chance of success.

Having established the framework of his new heaven and earth Marduk, acting as the celestial architect, set to work to furnish them. In the first place he founded E-Sharra, or the mansion of heaven, and next he set apart and arranged proper places for the old gods of the three realms–Anu, Bel and Ea.

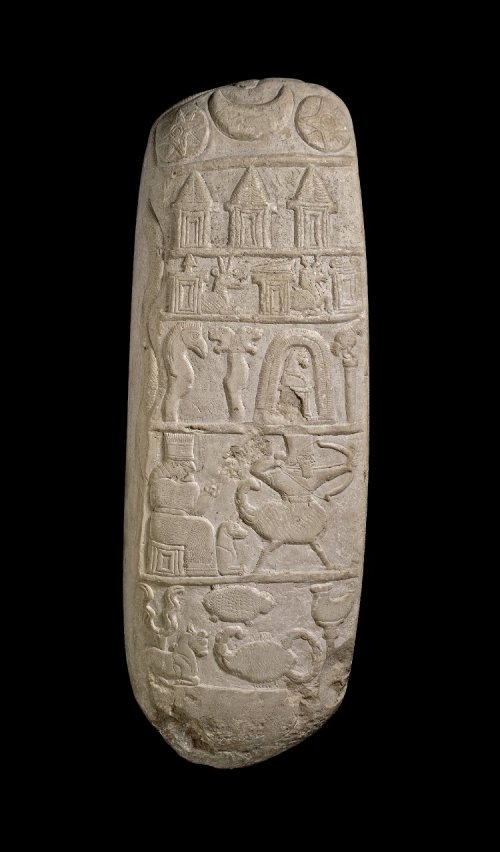

![Illustration: Tablet sculptured with a scene representing the worship of the Sun-god in the Temple of Sippar. The Sun-god is seated on a throne within a pavilion holding in one hand a disk and bar which may symbolize eternity. Above his head are the three symbols of the Moon, the Sun, and the planet Venus. On a stand in front of the pavilion rests the disk of the Sun, which is held in position by ropes grasped in the hands of two divine beings who are supported by the roof of the pavilion. The pavilion of the Sun-god stands on the Celestial Ocean, and the four small disks indicate either the four cardinal points or the tops of the pillars of the heavens. The three figures in front of the disk represent the high priest of Shamash, the king (Nabu-aplu-iddina, about 870 B.C.) and an attendant goddess. [No. 91,000.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00582752_001_l.jpg?w=500)

Illustration: Tablet sculptured with a scene representing the worship of the Sun-god in the Temple of Sippar.

The Sun-god is seated on a throne within a pavilion holding in one hand a disk and bar which may symbolize eternity.

Above his head are the three symbols of the Moon, the Sun, and the planet Venus.

On a stand in front of the pavilion rests the disk of the Sun, which is held in position by ropes grasped in the hands of two divine beings who are supported by the roof of the pavilion.

The pavilion of the Sun-god stands on the Celestial Ocean, and the four small disks indicate either the four cardinal points or the tops of the pillars of the heavens.

The three figures in front of the disk represent the high priest of Shamash, the king (Nabu-aplu-iddina, about 870 B.C.) and an attendant goddess. [No. 91,000.]

Museum number 91000

The engraved text contains a record of Nabu-apla-iddina’s re-endowment of the Sun-Temple at Sippar. The inscription is engraved in six columns, three upon the obverse and three upon the reverse; and the upper part of the obverse is occupied by a scene sculptured in low relief; the edges of the tablet are bevelled.

Museum number 91000

Group of Objects

Pottery box and the limestone sun-god tablet and its covers deposited in it by Nabopolassar.

The text of the Fifth Tablet, which would undoubtedly have supplied details as to Marduk’s arrangement and regulations for the sun, the moon, the stars, and the Signs of the Zodiac in the heavens is wanting.

The prominence of the celestial bodies in the history of creation is not to be wondered at, for the greater number of the religious beliefs of the Babylonians are grouped round them. Moreover, the science of astronomy had gone hand in hand with the superstition of astrology in Mesopotamia from time immemorial; and at a very early period the oldest gods of Babylonia were associated with the heavenly bodies.

Thus the Annunaki and the Igigi, who are bodies of deified spirits, were identified with the stars of the northern and southern heaven, respectively. And all the primitive goddesses coalesced and were grouped to form the goddess Ishtar, who was identified with the Evening and Morning Star, or Venus.

The Babylonians believed that the will of the gods was made known to men by the motions of the planets, and that careful observation of them would enable the skilled seer to recognize in the stars favourable and unfavourable portents. Such observations, treated from a magical point of view, formed a huge mass of literature which was being added to continually.

From the nature of the case this literature enshrined a very considerable number of facts of pure astronomy, and as early as the period of the First Dynasty (about 2000 B.C.), the Babylonians were able to calculate astronomical events with considerable accuracy, and to reconcile the solar and lunar years by the use of epagomenal months.

They had by that time formulated the existence of the Zodiac, and fixed the “stations” of the moon, and the places of the planets with it; and they had distinguished between the planets and the fixed stars. In the Fifth Tablet of the Creation Series (l. 2) the Signs of the Zodiac are called Lumashi, but unfortunately no list of their names is given in the context.

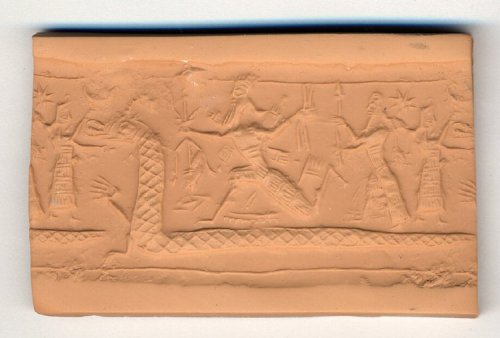

![Illustration: Tablet inscribed with a list of the Signs of the Zodiac. [No. 77,821.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/015.png?w=500)

Illustration: Tablet inscribed with a list of the Signs of the Zodiac. [No. 77,821.]

Now these are supplied by the little tablet (No. 77,821) of the Persian Period of which a reproduction is here given. It has been referred to and discussed by various scholars, and its importance is very great. The transcript of the text, which is now published (see p. 68) for the first time, will be acceptable to the students of the history of the Zodiac.

Egyptian, Greek, Syriac and Arabic astrological and astronomical texts all associate with the Signs of the Zodiac twelve groups, each containing three stars, which are commonly known as the “Thirty-six Dekans.”

The text of line 4 of the Fifth Tablet of the Creation Series proves that the Babylonians were acquainted with these groups of stars, for we read that Marduk “set up for the twelve months of the year three stars apiece.” In the List of Signs of the Zodiac here given, it will be seen that each Sign is associated with a particular month.

At a later period, say about 500 B.C., the Babylonians made some of the gods regents of groups of stars, for Enlil ruled 33 stars, Anu 23 stars, and Ea 15 stars. They also possessed lists of the fixed stars, and drew up tables of the times of their heliacal risings.

Such lists were probably based upon very ancient documents, and prove that the astral element in Babylonian religion was very considerable.”

E.A. Wallis Budge, et al, & the British Museum, The Babylonian Legends of the Creation & the Fight Between Bel & the Dragon Told by Assyrian Tablets from Nineveh (BCE 668-626), 1901, pp. 10-11.

![Illustration: Tablet sculptured with a scene representing the worship of the Sun-god in the Temple of Sippar. The Sun-god is seated on a throne within a pavilion holding in one hand a disk and bar which may symbolize eternity. Above his head are the three symbols of the Moon, the Sun, and the planet Venus. On a stand in front of the pavilion rests the disk of the Sun, which is held in position by ropes grasped in the hands of two divine beings who are supported by the roof of the pavilion. The pavilion of the Sun-god stands on the Celestial Ocean, and the four small disks indicate either the four cardinal points or the tops of the pillars of the heavens. The three figures in front of the disk represent the high priest of Shamash, the king (Nabu-aplu-iddina, about 870 B.C.) and an attendant goddess. [No. 91,000.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00582752_001_l.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration: Tablet inscribed with a list of the Signs of the Zodiac. [No. 77,821.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/015.png?w=500)

![Illustration: Shamash the Sun-god setting (?) on the horizon. In his right he holds a tree (?), and in his left a ... with a serrated edge. Above the horizon is a goddess who holds in her left hand an ear of corn. On the right is a god who seems to be setting free a bird from his right hand. Round him is a river with fish in it, and behind him is an attendant god; under his foot is a young bull. To the right of the goddess stand a hunting god, with a bow and lasso, and a lion. From the seal-cylinder of Adda ..., in the British Museum. About 2500 B.C. [No. 89,115.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00135126_001_l.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration: Shamash the Sun-god rising on the horizon, flames of fire ascending from his shoulder. The two portals of the dawn, each surmounted by a lion, are being drawn open by attendant gods. From a Babylonian seal cylinder in the British Museum. [No. 89,110.]](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/an00323246_001_l.jpg?w=500)

begins with a description of the Creation and then goes on to describe a Flood, and there is little doubt that certain passages in this text are the originals of the Babylonian version as given in the Seven Tablets.

begins with a description of the Creation and then goes on to describe a Flood, and there is little doubt that certain passages in this text are the originals of the Babylonian version as given in the Seven Tablets. .

. , Ilu Nagar Ilu Nagar, i.e., “the workmen gods,” about whom nothing is known.

, Ilu Nagar Ilu Nagar, i.e., “the workmen gods,” about whom nothing is known.