Sex, Evil, and the Fall

“If we posit a rich circulation of oral traditions in the eastern Mediterranean–including Mesopotamia, West Semitic cultures, and Greece–following the well-attested trade route in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages, then we may wish to relate these Greek, Mesopotamian, and biblical texts to these (now invisible) streams of tradition.

In this view, the texts are a literary selection and / or reworking of a few stories among the many variations that circulated in these traditions. With this maximal view of the interaction of eastern Mediterranean oral and written traditions, it is not necessary to relate the surviving texts to each other directly; it is plausible to see each as representing a particular selection of motifs and combinations, each text articulating its distinctive discourse out of the available materials of tradition.

Against this background, we may see Genesis 6:1-4 as related to Greek traditions as a member of a larger family of discourses, and, at the same time, as a distinctive version (and abbreviation) of old traditions.

It has often been argued that the biblical writers eschewed mythology and embraced instead a view of time and history closer to modern conceptions. This position, exemplified in the “Biblical Theology” school of the postwar period has been effectively countered by closer attention to the continuities between biblical and Near Eastern texts and concepts.

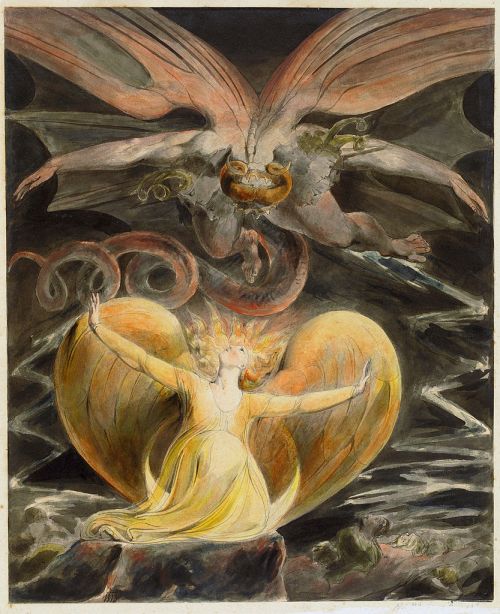

Satan in his Original Glory:

‘Thou wast Perfect till Iniquity was Found in Thee’

c.1805 William Blake 1757-1827 Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N05892

Genesis 1-11 functions as myth just as thoroughly as Atrahasis or Hesiod’s Theogony, in that it lays out the origin of the present cosmic order as a product of primeval events, a narrative of the past that is constitutive of the present world.

In Alan Dundes’ succinct defintion, myth is “a sacred narrative explaining how the world or humans came to be in their present form.” (Alan Dundes, ed., The Flood Myth (Berkeley, 1988), p. 1.) Genesis 1-11 fulfills neatly this generic and functional definition. It is a cycle of ancient Israelite mythology, a prelude to the stories (which may be called legendary or epic) of national origin in the rest of the Pentateuch. Genesis 6:1-4 is an obvious example of myth in this sense.

Even as Genesis 6:1-4 shows that mythology was alive and well in ancient Israel, it also shows that such stories could be controversial, since this account has been so severely truncated in the J source. Each culture creates its own discursive boundaries, which are constantly subject to negotiation and conflict.

William Blake, the Fall of Satan.

http://www.allpaintings.org/v/Romanticism/William+Blake/William+Blake+-+The+fall+of+Satan.jpg.html

There were aspects of the full story of the Sons of God and the Daughters of Men that, according to the J source, ought not to be said. The boundaries between what can and cannot be said are important to discern in order to attend to the distinctive features of Israelite culture in its various manifestations.

Israelite religion is both like and unlike the religions of its neighbors according to these shifting boundaries of discourse and practice. Genesis 6:1-4 shows how the sexuality of the gods and their marriages with human women came into conflict with the unsayable in the conceptual horizons of the J source.

William Blake (1757–1827)

wikidata: Q41513 s:en:Author:William

Deutsch: Der große Rote Drache und die mit der Sonne bekleidete Frau

Français : Le grand Dragon Rouge et la Femme vêtue de soleil

Español: El gran dragón rojo y la mujer vestida de sol

wikidata:Q538936

Date 1805-1810

Current location: National Gallery of Art

wikidata:Q214867

Washington (D.C.)

Source/Photographer The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH.

Permission

(Reusing this file) http://mail.wikipedia.org/pipermail/wikide-l/2005-April/012195.html

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Blake_003.jpg

That these issues are not spoken of elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible also illuminates this particular boundary of the unsayable. Sex, gods, and the allure of women are a potent and self-censoring combination in biblical discourse.

In post-biblical times, these tantalizing issues came to receive fuller attention, in what Freud might call a return of the repressed. The terse and sensational aspects of Genesis 6:1-4 provoked detailed exegetical attention. The wayward Sons of God and the Nephilim, the latter taken in their etymological sense as the “fallen ones,” in combination with other biblical stories of the “fall” of divine beings (especially Isaiah 14, Ezekiel 28, and Psalm 82), gave rise to the myth of the fallen angels who seduced human women and introduced evil on the earth.

The awakened sexuality of these divine beings leads to their cosmic fall, similar to the exegetical equation of sex and evil in some post-biblical interpretations of the Garden of Eden story. (Elaine Pagels, Adam, Eve, and the Serpent, New York, 1988).

Through these extensions of the biblical story, the brief and cryptic text of Genesis 6:1-4 became the site of potent discourses in the Hellenistic period and beyond.”

Ronald Hendel, “The Nephilim Were on the Earth: Genesis 6:1-4 and its Ancient Near Eastern Context,” in Christoph Auffarth and Loren T. Stuckenbruck, eds., The Fall of the Angels, Brill, 2004, pp. 32-4.