Barbarian Wisdom and Berossus

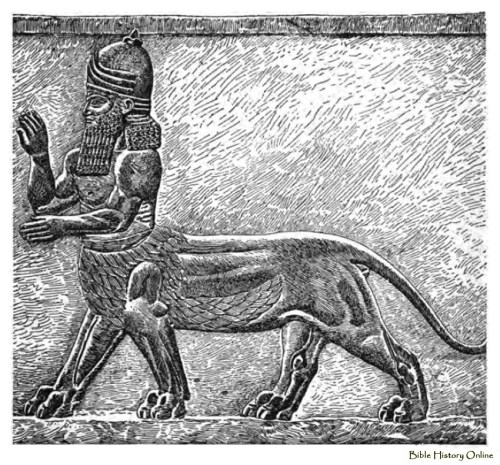

“Tiamat’s monsters were characterised by a mixture of animal and human features. If my reconstruction is broadly correct, Berossos filled the void left by their demise with separate creation accounts for each of these categories of being.

The Enūma Eliš has nothing to say about the creation of animals, but does describe human creation in some detail. Berossos agrees broadly with its account of human creation, though some details differ.

Above all, Berossos claims that Bel used his own blood to create mankind whereas in the epic Marduk uses that of another god. Berossos may or may not have found this version of events in now lost Mesopotamian texts, but the question remains why he introduced it here, against the pull of his main source.

The answer, one suspects, was once again that he was keen to cater for the tastes of his Greek readers. In Enūma Eliš, as in other Mesopotamian texts, mankind descends from a rebel against the emerging order of the universe.

Among other things, that explains why we must shoulder the gods’ work and lead a life of misery. In Berossos, this typically Babylonian view of human life is developed into one that would have spoken to educated Greeks: the blood that flows in our veins is not after all that of a devil but of Zeus no less: and so it is that we are endowed with νους (‘intelligence’), and divine φρόνησις (‘understanding’).

De Breucker points out that Berossos is here elaborating on an idea which he found in the Babylonian Poem of the Flood or Atrahasis, where the god (W)ē, ‘who has intelligence’ (Akkadian tēmu) is slaughtered to create man.

This is an interesting detail, for it shows that Berossos creatively combined diverse Babylonian sources. But he did more than merely cut and paste what he found: in the Babyloniaca the ruling god himself gives of his intelligence.

One last time, the preferred version of the story seems chosen for its resonances with Greek, and more specifically Stoic, thought. The Stoic god is himself νους, or νοερός. The same must be true of Bel in Berossos, for as recipients of his blood we too are νοεροί.

Indeed, we are also endowed with divine understanding, φρόνησις. In allegorical terms, Athena is φρόνησις, sprung from the head of Zeus, which may explain why decapitation becomes an issue in Berossos whereas it plays no role in Enūma Eliš or Atrahasis: the story which describes Zeus giving birth to Athena / Phronesis from his head was much-discussed in Stoic circles from Greece to Babylon itself. Berossos, it would seem, alludes to it here.

There is much in the Babyloniaca that will remain forever lost to us. The extant fragments are scanty, and often do not allow us to reconstruct with certainty what Berossos wrote, or even what he intended. That is a fact which must be accepted.

But I also hope to have shown that progress can be made; and that, through careful and sympathetic reading, we can often gain a fairly good sense of what Berossos was trying to achieve. I have argued that Book 1 of the Babyloniaca was in many ways Berossos’ signature piece. It is here that he establishes his credentials as a conveyor of barbarian wisdom, one of the few subject positions that were available to a non-Greek wishing to address a Greek audience.

Already Aristotle thought that the Chaldaeans were among those who invented philosophy, so for once Berossos had a positive stereotype with which to work. He embraced the project with gusto, conjuring up the super-sage Oannes, who was equally at home in water and darkness as in daylight and air (who better to describe how these principles coalesced to form the cosmos?); and putting in the mouth of this creature a cosmogonic myth that could literally not have been more ancient: after all, Oannes appears in year one of human history.

Yet, ancient as it is, Oannes’ logos becomes philosophically fresh when read through Berossos’ rationalising lens. What is on display here is both age-old barbarian wisdom and cutting-edge Greek philosophy, or rather, a pretence to cutting-edge philosophy.

Stoic elements are predominant, partly because Stoicism was the best-selling brand of philosophy at the time, and partly, one suspects, because it lent itself to the project of educating a king. But Berossos does far more than simply default to the Stoa. He shows that he can do Empedocles too. Above all, he throws in outrageous intellectual feats of his own, none more outrageous than his numerical equation of Omorka / Tiamat with Selene, the moon (BNJ 680 F lb (6)).

This too has sometimes been branded an interpolation, but it strikes me as quintessential Berossos, precisely the kind of thing this author would do. Book 1 of the Babyloniaca was his opportunity to shine, and he made sure he took it. Abydenos was right to summarises the contents of the book as ‘the wisdom of the Chaldaeans’ (BNJ 685 F2b). That is surely how Berossos intended it.”

Johannes Haubold, “The Wisdom of the Chaldaeans: Reading Berossos, Babyloniaca Book 1,” from Johannes Haubold, Giovanni B. Lanfranchi, Robert Rollinger, John Steele (eds.), The World of Berossos, Proceedings of the 4th International Colloquium on the Ancient Near East Between Classical and Ancient Oriental Traditions, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2013, pp. 41-3.