Gane: Neo-Babylonian Monsters, Demons & Dragons From a Narrow Slice of Time & Space

A number of scholars have already correlated Mesopotamian iconography with cuneiform texts to identify and illuminate composite beings over a wide range of periods in terms of their historical development, association with deities, and impact on humans within ancient systems of religion and mythology.

The present research draws heavily on their work, but uniquely focuses on basically synchronic, tightly controlled, comprehensive analysis of the iconographic repertoire of hybrid beings in a narrow slice of time and space.

Mesopotamian composite beings have been the focus of several formative works. One of the most influential scholars in the field has been Frans A. M. Wiggermann.

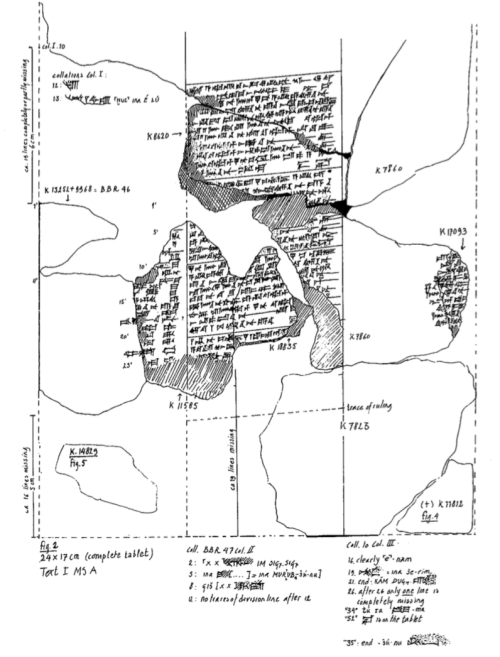

This is Figure 2, K2987B+ and K9968+, from Professor F.A.M. Wiggermann, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts, 1992, pp. 195-7.

In his Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts (1992), he examines the identities and histories of those Mesopotamian supernatural creatures mentioned in the Neo-Assyrian texts K 2987B+ and KAR 298.

Regarding this partial representation of all Mesopotamian hybrids, Wiggermann summarizes:

“The texts treated are rituals for the defence of the house against epidemic diseases, represented as an army of demonic intruders. The gates, rooms, and corners of the house are occupied by prophylactic figures of clay or wood, that the texts describe in detail.”

(Frans A. M. Wiggermann, Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts (CM 1; Groningen: Styx & PP, 1992), p. xii. (This is a second edition of Wiggermann’s dissertation, originally published as Babylonian Prophylactic Figures: The Ritual Texts [Amsterdam: Free University Press, 1986].)

As he points out, these figures described in the texts have been discovered in archaeological excavations, providing a significant link between text and material remains.

Although Wiggermann’s monograph is difficult to navigate (due to the nature of its organization), it has been the backbone of much of my research.

An excerpt from the introduction to F.A.M. Wiggermann’s Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts, 1992, p. xi.

An important systematic treatment of composite creatures by Wiggermann is his 1997 Reallexikon der Assyriologie (RlA) article titled “Mischwesen. A. Philologisch. Mesopotamien.”

(Frans A. M. Wiggermann, “Mischwesen. A. Philologisch. Mesopotamien,” Reallexikon der Assyriologie (RlA) 8:222-246.)

Here he provides numerous textual, philological, and archaeological examples of most of the known Mesopotamian creatures, and clarifies terms for categories.

Modern scholarship identifies distinct categories of subdivine (but superhuman) creatures. Those that walk on all fours, like quadruped natural animals, are identified as monsters while those that walk on two legs, like humans, are designated as demons.

Dragons, which belong to a separate class, are hybrid creatures that are essentially snakes.

(Cf. Joan G. Westenholz, ed., Dragons, Monsters, and Fabulous Beasts (Jerusalem: Bible Lands Museum, 2004), p. 11.)

According to Wiggermann, monsters are neither gods nor demons.

(Wiggermann, “Mischwesen. A,” RlA 8:231.)

Although their names are occasionally written with the divine determinative, they usually do not wear the horned crown of divinity.

They are not included in god-lists, not found in the list of “evil spirits” (utukkū lemnūti), and not mentioned in medical texts as demons of diseases.”

(Cf. Chikako E. Watanabe, Animal Symbolism in Mesopotamia: A Contextual Approach (WOO 1; Vienna: Institut für Orientalistik der Universität Wien, 2002), p. 39.)

Constance Ellen Gane, Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, Doctoral Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 2012, pp. 2-3.