Kvanvig: Initiation is a Restriction of Marduk

“We think van der Toorn is right in taking this as a comment to the tendency present in the Catalogue. This is still no absolute chronology, since apkallus are listed as authors in III, 7; IV, 11; and VI, 11.

Nevertheless, the commentary seems to underscore three stages in the transmission of highly recognized written knowledge: it starts in the divine realm with the god of wisdom Ea; at the intersection point between the divine and the human stands Uanadapa; and as the third link in this chain stands (we must presuppose) an ummanu, “scholar.”

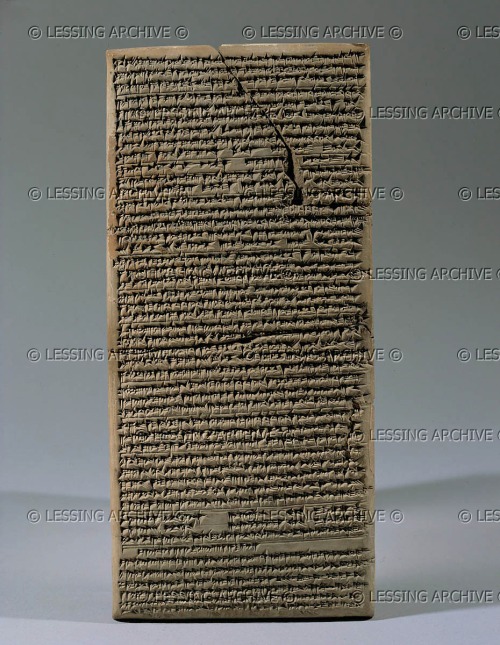

Tablet of Uruk. The ritual of daily sacrifices in the temple of the god Anu in Uruk.

Seleucid period, 3rd-2nd Centuries BCE, Hellenistic, from Uruk.

Baked clay, 22,3 x 10,4 cm

Louvre, AO 6451.

A. Lenzi has called attention to a colophon to a medical text which reveals a similar kind of transmission:

“Salves (and) bandages: tested (and) checked, which are ready at hand, composed by the ancient apkallus from before the flood, which in Šuruppak in the second year of Enlil-bani, king of Isin, Enlil-muballit, apkallu of Nippur, bequeathed. A non-expert may show an expert. An expert may not show a non-expert. A restriction of Marduk.”

(Medical Text, AMT 105, 1, 21-5. Lenzi, Secrecy and the Gods, p. 117.)

The models of transmission in the commentary of the Catalogue and in this colophon are not exactly the same, but the tendency is. In this text, an expert, possibly an āšipu, has in his hands a tablet of high dignity: it belongs to the secrets of the gods (cf. below).

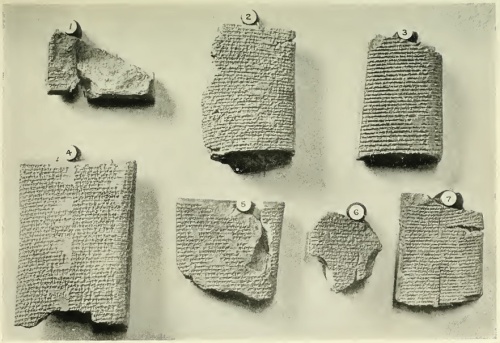

![AM-102 ; No. #1 (K4023) British Museum of London

Tablet K.4023 COL. I [Starting on Line 38] . . . Root of caper which (is) on a grave, root of thorn (acacia) which (is) on a grave, right horn of an ox, left horn of a kid, seed of tamarisk, seed of laurel, Cannabis, seven drugs for a bandage against the Hand of a Ghost thou shalt bind on his temples. FOOTNOTES: [1] - The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 54, No. 1/4 (Oct., 1937), pp. 12-40; Assyrian Prescriptions for the Head By R. Campbell Thompson

http://antiquecannabisbook.com/chap2B/Assyria/K4023.htm](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/k4023-antdiluvian-medical-text.jpg?w=500)

AM-102 ; No. #1 (K4023)

British Museum of London

Tablet K.4023

COL. I

[Starting on Line 38] . . .

Root of caper which (is) on a grave, root of thorn (acacia) which (is) on a grave, right horn of an ox, left horn of a kid, seed of tamarisk, seed of laurel, Cannabis, seven drugs for a bandage against the Hand of a Ghost thou shalt bind on his temples.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] – The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 54, No. 1/4 (Oct., 1937), pp. 12-40; Assyrian Prescriptions for the Head By R. Campbell Thompson

http://antiquecannabisbook.com/chap2B/Assyria/K4023.htm

Therefore, if somebody not belonging to the initiated by accident should have such a tablet, he may show it to the expert, but the expert should never show it to an uninitiated person. The content of the tablet was secret; it went back to the ancient apkallus from before the flood.

Afterwards a distinguished sage, an apkallu in Nippur, inherited it, and from this line of transmission it arrived to the scholar writing this colophon. The division between the apkallus before the flood and the postdiluvian apkallu in Nippur may here be similar to the division of the first group of apkallus of divine descent and the next group of four apkallus of human descent in Bīt Mēseri.

As we have seen, the Late Babylonian Uruk tablet also had a division between a group of seven “before the flood” and a group of ten afterwards, but here the first seven were apkallus, and the next group (with one or two exceptions) were ummanus.

What we observe here is confirmed by two independent contributions with different scope that we already have called attention to, K. van der Toorn, Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible, and A. Lenzi, Secrecy and the Gods.

They are both concerned with the transition from oral transmission of divine messages to written revelations, and they both use Mesopotamian sources from the first millennium as an analogy to what took place in Israel in the formation of the Hebrew Bible.

(van der Toorn, Scribal Culture, pp. 205-21; Lenzi, Secrecy and the Gods, pp. 67-122.)

Enuma Elish means “when above”, the two first words of the epic.

This Babylonian creation story was discovered among the 26,000 clay tablets found by Austen Henry Layard in the 1840’s at the ruins of Nineveh.

Enuma Elish was made known to the public in 1875 by the Assyriologist George Adam Smith (1840-76) of the British Museum, who was also the discoverer of the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh. He made several of his findings on excavations in Nineveh.

http://www.creationmyths.org/enumaelish-babylonian-creation/enumaelish-babylonian-creation-3.htm

Van der Toorn is concerned about the broad tendency in Mesopotamian scholarly series from the end of the second millennium to classify these as nisirti šamê u erseti, “a secret of heaven and earth.” This expression, occurring in colophons and elsewhere, does two things to the written scholarly lore: on the one hand, it claims that this goes back to a divine revelation; on the other hand, it restricts this revelation to a defined group of scholars.

This tendency goes along with the tendency to date the written wisdom back to primeval time, or to the time before the flood. This also concerns the most well-known compositions from the end of the second millennium, Enuma Elish and the standard version of Gilgamesh.”

Helge Kvanvig, Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, Brill, 2011, pp. 149-51.