Lenzi: More on the Exaltation of the Anu Cult

“Beaulieu believes this development also provides an explanation for the great number of scholarly texts that have turned up in Seleucid-level excavations at Uruk, both traditional kinds known from elsewhere as well as those with an explicitly Urukean bias.

(See François Thureau-Dangin, Tablettes d’Uruk à l’usage des Prêtres du Temple d’Anu au Temps des Séleucides, Textes Cunéiformes du Louvre 6 (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1922) (= TCL 6); SpBTU 1-5, BaMB 2, etc. The Uruk Prophecy is an example of a distinctively Urukean text.)

In fact, as Beaulieu explains, one colophon, attached to TCL 6 38, seems to offer justification for the new rituals of the Anu cult via the familiar “pious fraud” trick: Kidin-Anu “found” some ritual tablets in Elam, where the sinister Nabopolassar had taken them much earlier. He copied them there in order to return to Uruk and properly restore the Anu cult.

(See Beaulieu, “Uruk Prophecy,” 47 for the analysis. The text may be found in Thureau-Dangin, Rituels Accadiens, 79-80, 85-86 and Hunger, Babylonische und assyrische Kolophone, #107.)

The archaizing tendency was also deployed in Kephalon’s temple dedicatory inscription from 201 BCE mentioned above. (Also mentioned by Beaulieu in connection with antiquarianism (see “Antiquarian Theology,” 68).

Although not so much as hinted at in the earlier Nikarchos inscription of 244 BCE, the later inscription names Adapa himself, the first of the antediluvian apkallū, as the founder of the Bīt Rēs temple. (See Falkenstein, Topographie, 6 and van Dijk, “Die Inschriftenfunde,” 47 (improving Falkenstein) for the text.)

With this and the other two contextual points in mind, we may now attempt to answer the questions I posed at the beginning of this study.

The ULKS clearly draws upon earlier ideas to formulate its list. What I have emphasized in the foregoing is that its formulation of the list, although unique, is better viewed not as a new invention from old material, but as a very systematic and explicit formulation of an old association, one that is evidenced already in early first millennium materials.

Given the deliberate and learned antiquarian interests identified in texts by Beaulieu, it seems quite reasonable to include the ULKS in that intellectual current, too.

Thus, just as the scholars responsible for moving Anu to the head of the pantheon utilized the Kassite period An = Anum god-list for that purpose, so too they used earlier traditions about apkallū–ummânū relations to further their religious authority and other aspects of their agenda, especially their standing vis-à-vis political leadership.

A scrutiny of the precise manner in which the scribes behind the ULKS formulated their genealogy reveals the cultic and especially political aspects of their aspirations.

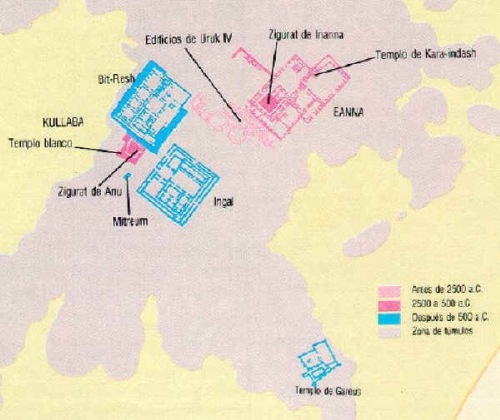

An aerial view of the Uruk ziggurat. My purpose in posting pics of the temple remains in Ur and Uruk is to compare their relative sizes and comparative majesty.

As for the cultic aspect of the agenda, it is surely significant that Nungalpirigal, the first postdiluvian apkallū, makes a bronze lyre that finds its final resting place in front of Anu. This creates a connection between our text and the renewal of the cult of Anu as discussed by Beaulieu.

But there is more to matters than this simple fact. By placing this cultic act of devotion first in the list, right after the flood, the ULKS intends to give the Anu cult prominence; the first human sage was a devotee of Anu.

Moreover, the list probably supplies an etiology for the relationship between Nungalpirigal, the Eana temple, and Anu, thus answering any would be critics of the novel idea that Anu’s house could displace Eana.”

Alan Lenzi, The Uruk List of Kings and Sages and Late Mesopotamian Scholarship, JANER 8.2, Brill, Leiden, 2008. pp. 160-1.