Gane: Applying Black’s Theory of Metaphor

“Composite creatures are found on various cosmic levels. For that reason, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography, by Wayne Horowitz (1998; rev. 2011), has informed the present study, especially with regard to the “Babylonian Map of the World” and Enuma Elish texts, which mention a significant number of mixed beings found in the Neo-Babylonian iconographic repertoire.

This cuneiform inscription and map of the Mesopotamian world depicts Babylon in the center, ringed by a global ocean termed the “salt sea.” The map portrays eight regions, though portions are missing, while the text describes the regions, and the mythological creatures and legendary heroes that live in them. Sippar, Babylonia, 700 – 500 BCE.

Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin. Licensed under the Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareaAlike license.

http://www.ancient.eu/image/2287/

(Wayne Horowitz, Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography (Mesopotamian Civilizations 8; Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1998).

Regarding Sumero-Babylonian religion in ancient Mesopotamia, two foundational studies are Wilfred Lambert’s essay on “The Historical Development of the Mesopotamian Pantheon: A Study in Sophisticated Polytheism” (1975) and Thorkild Jacobsen’s trail-blazing book titled The Treasures of Darkness (1976).

Enuma Elish means “when above”, the two first words of the epic.

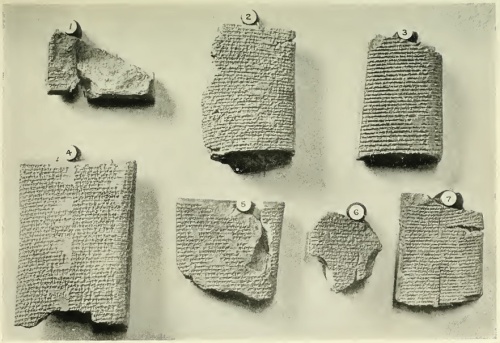

This Babylonian creation story was discovered among the 26,000 clay tablets found by Austen Henry Layard in the 1840’s at the ruins of Nineveh.

Enuma Elish was made known to the public in 1875 by the Assyriologist George Adam Smith (1840-76) of the British Museum, who was also the discoverer of the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh. He made several of his findings from excavations in Nineveh.

http://www.creationmyths.org/enumaelish-babylonian-creation/enumaelish-babylonian-creation-3.htm

(Wilfred G. Lambert, “The Historical Development of the Mesopotamian Pantheon: A Study in Sophisticated Polytheism,” in Unity in Diversity: Essays in the History, Literature, and Religion of the Ancient Near East (ed. Hans Goedicke and J. J. M. Roberts; Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), pp. 191-200.)

(Thorkild Jacobsen, The Treasures of Darkness (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976).

Since these publications appeared, still others have contributed to a greater understanding of the complexities of Mesopotamian religion, with its thousands of named gods and demons, but a comprehensive, systematic understanding still eludes modern scholarship.

Of particular importance to the methodological framework of the present research are the works of two scholars, Chikako E. Watanabe and Mehmet-Ali Ataç.

Watanabe’s Animal Symbolism in Mesopotamia: A Contextual Approach (2002), drawing upon her doctoral dissertation (University of Cambridge, 1998), aims “to examine how animals are used as ‘symbols’ in Mesopotamian culture and to focus on what is intended by referring to animals in context.”

(Watanabe, Animal Symbolism in Mesopotamia, Institut für Orientalistik d. Univ., 2002, p. 1.

Zu or Anzu (from An ‘heaven’ and Zu ‘to know’ in Sumerian language), as a lion-headed eagle, ca. 2550–2500 BCE, Louvre.

Votive relief of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, representing the bird-god Anzu (or Im-dugud) as a lion-headed eagle.

Alabaster, Early Dynastic III (2550–2500 BCE). Found in Telloh, ancient city of Girsu.

H. 21.6 cm (8 ½ in.), W. 15.1 cm (5 ¾ in.), D. 3.5 cm (1 ¼ in.)

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2013/07/legend-of-anzu-which-stole-tablets-of.html

The scope of her investigation is limited to the symbolic aspects of two natural animals, the lion and bull, and two composite creatures, the Anzu bird and the horned lion-griffin. Watanabe’s narrow but deep analysis provides an excellent paradigm for study of Mesopotamian iconographic creatures in general.

Watanabe maintains that “the best way to interpret meanings belonging to the past is to pay close attention to the particular contexts in which symbolic agents occur.”

She does this through application of an approach known as the interaction view of metaphor, also called the theory of metaphor, developed by Max Black.

According to Watanabe, this approach aims to interpret the meanings of objects, whether occurring in figurative statements or iconographic representations, from within the contexts of their original functions, “by examining their internal relationships with other ideas or concepts expressed within the same contextual framework.”

As she points out, “the treatment of symbolic phenomena on a superficial level” does “not explain the function of symbolism.”

Watanabe observes that the names of animals mentioned in ancient texts generally carry meaning beyond references to the natural creatures themselves.

When a creature is repeatedly found in a specific context, this context provides a link or clue to the meaning attached to it.

Watanabe’s treatment of composite creatures, the Imdugud/Anzu and the horned lion-griffin, in Chapter 5 of her work provides a case study for analysis of similar mixed beings.

Each composite creature is derived from two or more species, with each animal part embodying a concept associated with the given animal’s natural behavior.

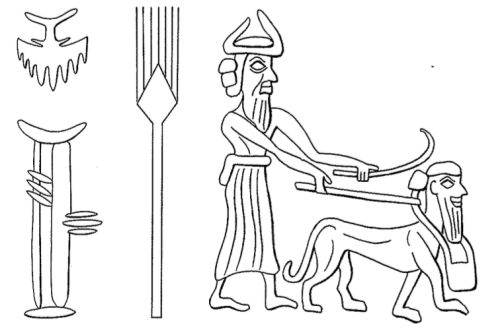

This illustration of a god walking his human-headed lion lacks the wings on the lion mentioned in Watanabe’s example. A detail from a cylinder seal of the Akkadian period, this exemplar is from Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons & Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, 1992, p. 39.

Thus, for instance, a winged, human-headed lion possesses attributes that include human intelligence, leonine power and ferocity, and eagle wings to provide swiftness and access to the realm of the sky.

Watanabe finds that “the study of these animals provides a model for the way in which the characteristics of two or more animals are integrated into one animal body, as a result of which multiple divine aspects, perceived in one deity, are effectively conveyed by a single symbolic animal.”

Wings are a frequent physical component of Mesopotamian composite creatures. Watanabe maintains that when animals that are ordinarily wingless are portrayed with wings, the intent in some cases may be to represent the constellation that is symbolized by that creature.

Constellations of stars were understood by the Babylonians as images of “earthly objects projected onto the evening sky.”

(Cf. Hope B. Werness, The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in Art (New York: Continuum, 2006), p. 433.)

Additionally, wings could personify the abstract concepts of wind or the flying of time. While wings often belong to the realm of the gods, they can also be associated with night, death, and evil.”

Constance Ellen Gane, Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, Doctoral Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 2012, pp. 5-6.

![In 1847 archaeologists discovered a prism of Sargon dated to the early 8th century BC reading: "At the beginning of my royal rule, I…the town of the Samarians I besieged, conquered (2 Lines destroyed) [for the god…] who let me achieve this my triumph… I led away as prisoners [27,290 inhabitants of it (and) equipped from among them (soldiers to man)] 50 chariots for my royal corps…. The town I rebuilt better than it was before and settled therein people from countries which I had conquered. I placed an officer of mine as governor over them and imposed upon them tribute as is customary for Assyrian citizens." (Nimrud Prism IV 25-41) https://theosophical.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg](https://therealsamizdat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/sargon-nimrud-cylinder1.jpg?w=500)