Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Nameless Harlot

THE EPIC OF GILGAMISH.

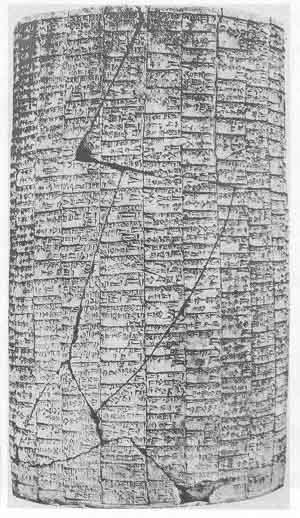

“The narrative of the life, exploits and travels of Gilgamish, king of Erech, filled Twelve Tablets which formed the Series called from the first three words of the First Tablet, SHA NAGBU IMURU, i.e., “He who hath seen all things.”

The exact period of the reign of this king is unknown, but in the list of the Sumerian kingdoms he is fifth ruler in the Dynasty of Erech, which was considered the second dynasty to reign after the Deluge. He was said to have ruled for 126 years.

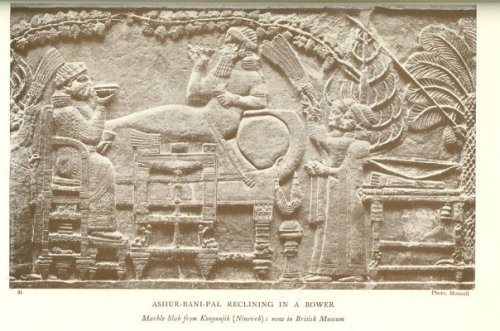

The principal authorities for the Epic are the numerous fragments of the tablets that were found in the ruins of the Library of Nebo and the Royal Library of Ashur-bani-pal at Nineveh, and are now in the British Museum, but very valuable portions of other and older versions (including some fragments of a Hittite translation) have now been recovered from various sources, and these contribute greatly to the reconstruction of the story.

The contents of the Twelve Tablets may be briefly described thus–

The opening lines describe the great knowledge and wisdom of Gilgamish, who saw everything, learned everything, under stood everything, who probed to the bottom the hidden mysteries of wisdom, and who knew the history of everything that happened before the Deluge.

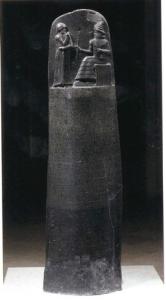

He travelled far over sea and land, and performed mighty deeds, and then he cut upon a tablet of stone an account of all that he had done and suffered. He built the wall of Erech, founded the holy temple of E-Anna, and carried out other great architectural works.

He was a semi-divine being, for his body was formed of the “flesh of the gods,” and “two-thirds of him were god, and one-third was man,” The description of his person is lost. As Shepherd (i.e., King) of Erech he forced the people to toil overmuch, and his demands reduced them to such a state of misery that they cried out to the gods and begged them to create some king who should control Gilgamish and give them deliverance from him.

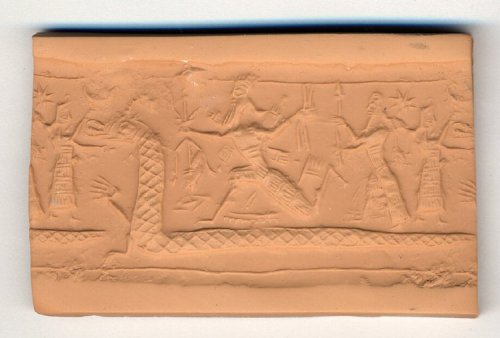

The gods hearkened to the prayer of the men of Erech, and they commanded the goddess Aruru to create a rival to Gilgamish. The goddess agreed to do their bidding, and having planned in her mind what manner of being she intended to make, she washed her hands, took a piece of clay, cast it on the ground, and made a male creature like the god En-urta. His body was covered all over with hair. The hair of his head was long like that of a woman, and he wore clothing like that of Sumuqan, the god of cattle.

He was different in every way from the people of the country, and his name was Enkidu. He lived in the forests on the hills, ate herbs like the gazelle, drank with the wild cattle, and herded with the beasts of the field. He was mighty in stature, invincible in strength, and obtained complete mastery over all the creatures of the forests in which he lived.

One day a certain hunter went out to snare game, and he dug pit-traps and laid nets, and made his usual preparations for roping in his prey. But after doing this for three days he found that his pits were filled up and his nets smashed, and he saw Enkidu releasing the beasts that had been snared.

The hunter was terrified at the sight of Enkidu, and went home hastily and told his father what he had seen and how badly he had fared. By his father’s advice he went to Erech, and reported to Gilgamish what had happened.

When Gilgamish heard his story he advised him to act upon a suggestion which the hunter’s father had already made, namely that he should hire a harlot and take her out to the forest, so that Enkidu might be ensnared by the sight of her beauty, and take up his abode with her.

The hunter accepted this advice, and having found a harlot to help him in removing Enkidu from the forests, he set out from Erech with her and in due course arrived at the forest where Enkidu lived, and sat down by the place where the beasts came to drink.

On the second day when the beasts came to drink and Enkidu was with them, the woman carried out the instructions which the hunter had given her, and when Enkidu saw her cast aside her veil, he left his beasts and came to her, and remained with her for six days and seven nights. At the end of this period he returned to the beasts with which he had lived on friendly terms, but as soon as the gazelle winded him they took to flight, and the wild cattle disappeared into the woods.”

E.A. Wallis Budge, The Babylonian Story of the Deluge and the Epic of Gilgamish, 1929, pp. 41-3.

begins with a description of the Creation and then goes on to describe a Flood, and there is little doubt that certain passages in this text are the originals of the Babylonian version as given in the Seven Tablets.

begins with a description of the Creation and then goes on to describe a Flood, and there is little doubt that certain passages in this text are the originals of the Babylonian version as given in the Seven Tablets. .

. , Ilu Nagar Ilu Nagar, i.e., “the workmen gods,” about whom nothing is known.

, Ilu Nagar Ilu Nagar, i.e., “the workmen gods,” about whom nothing is known.