” … A girl might also obtain a limited degree of freedom by taking vows of celibacy and becoming one of the vestal virgins, or nuns, who were attached to the temple of the sun god. She did not, however, live a life of entire seclusion.

If she received her due proportion of her father’s estate, she could make business investments within certain limits. She was not, for instance, allowed to own a wineshop, and if she even entered one she was burned at the stake. Once she took these vows she had to observe them until the end of her days.

If she married, as she might do to obtain the legal status of a married woman and enjoy the privileges of that position, she denied her husband conjugal rites, but provided him with a concubine who might bear him children, as Sarah did to Abraham.

These nuns must not be confused with the unmoral women who were associated with the temples of Ishtar and other love goddesses of shady repute.

The freedom secured by a married woman had its legal limitations. If she became a widow, for instance, she could not remarry without the consent of a judge, to whom she was expected to show good cause for the step she proposed to take.

Punishments for breaches of the marriage law were severe. Adultery was a capital crime; the guilty parties were bound together and thrown into the river.

If it happened, however, that the wife of a prisoner went to reside with another man on account of poverty, she was acquitted and allowed to return to her husband after his release. In cases where no plea of poverty could be urged the erring women were drowned.

The wife of a soldier who had been taken prisoner by an enemy was entitled to a third part of her husband’s estate if her son was a minor, the remainder was held in trust. The husband could enter into possession of all his property again if he happened to return home.

Divorce was easily obtained. A husband might send his wife away either because she was childless or because he fell in love with another woman. Incompatibility of temperament was also recognized as sufficient reason for separation. A woman might hate her husband and wish to leave him.

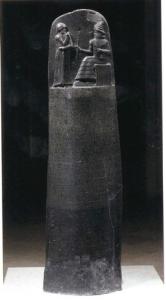

“If,” the Code sets forth, “she is careful and is without blame, and is neglected by her husband who has deserted her,” she can claim release from the marriage contract. But if she is found to have another lover, and is guilty of neglecting her duties, she is liable to be put to death.

A married woman possessed her own property. Indeed, the value of her marriage dowry was always vested in her. When, therefore, she divorced her husband, or was divorced by him, she was entitled to have her dowry refunded and to return to her father’s house. Apparently she could claim maintenance from her father.

A woman could have only one husband, but a man could have more than one wife. He might marry a secondary wife, or concubine, because he was without offspring, but “the concubine,” the Code lays down, “shall not rank with the wife.”

Another reason for second marriage recognized by law was a wife’s state of health. In such circumstances a man could not divorce his sickly wife. He had to support her in his house as long as she lived.

[ … ]

The legal rights of a vestal virgin were set forth in detail. If she had received no dowry from her father when she took vows of celibacy, she could claim after his death one-third of the portion of a son. She could will her estate to anyone she favoured, but if she died intestate her brothers were her heirs.

When, however, her estate consisted of fields or gardens allotted to her by her father, she could not disinherit her legal heirs. The fields or gardens might be worked during her lifetime by her brothers if they paid rent, or she might employ a manager on the “share system.”

Vestal virgins and married women were protected against the slanderer. Any man who “pointed the finger” against them unjustifiably was charged with the offense before a judge, who could sentence him to have his forehead branded.

It was not difficult, therefore, in ancient Babylonia to discover the men who made malicious and unfounded statements regarding an innocent woman. Assaults on women were punished according to the victim’s rank; even slaves were protected.

Women appear to have monopolized the drink traffic. At any rate, there is no reference to male wine sellers. A female publican had to conduct her business honestly, and was bound to accept a legal tender. If she refused corn and demanded silver, when the value of the silver by “grand weight” was below the price of corn, she was prosecuted and punished by being thrown into the water. Perhaps she was simply ducked.

As much may be inferred from the fact that when she was found guilty of allowing rebels to meet in her house, she was put to death.”

Donald A. Mackenzie, Myths of Babylonia and Assyria, 1915.